From Rural Wasteland to Urban Oasis

A History of Buckingham Pond

Buckingham Pond and Buckingham Lake Park, a five-acre pond surrounded by 15 acres of green space is a surprising urban oasis with a storied past. Board member Al Lawrence chronicles its history.

Tucked into a residential corner of Albany lies Buckingham Pond and Buckingham Lake Park, a five-acre pond surrounded by 15 acres of green space—a surprising urban oasis with a storied past. Al Lawrence, BPC Board Member, trawled through old maps, records, and newspaper archives to chronicle and bring you the history of this urban water body and park.

Beaver Creek (Before 1916)

The urban oasis now known as Buckingham Pond and Buckingham Lake Park traces its roots to the Beaverkill, or Beaver Creek, which once flowed from what is now the University at Albany campus, meandering through the Town of Bethlehem and the City of Albany to the Hudson River [1].

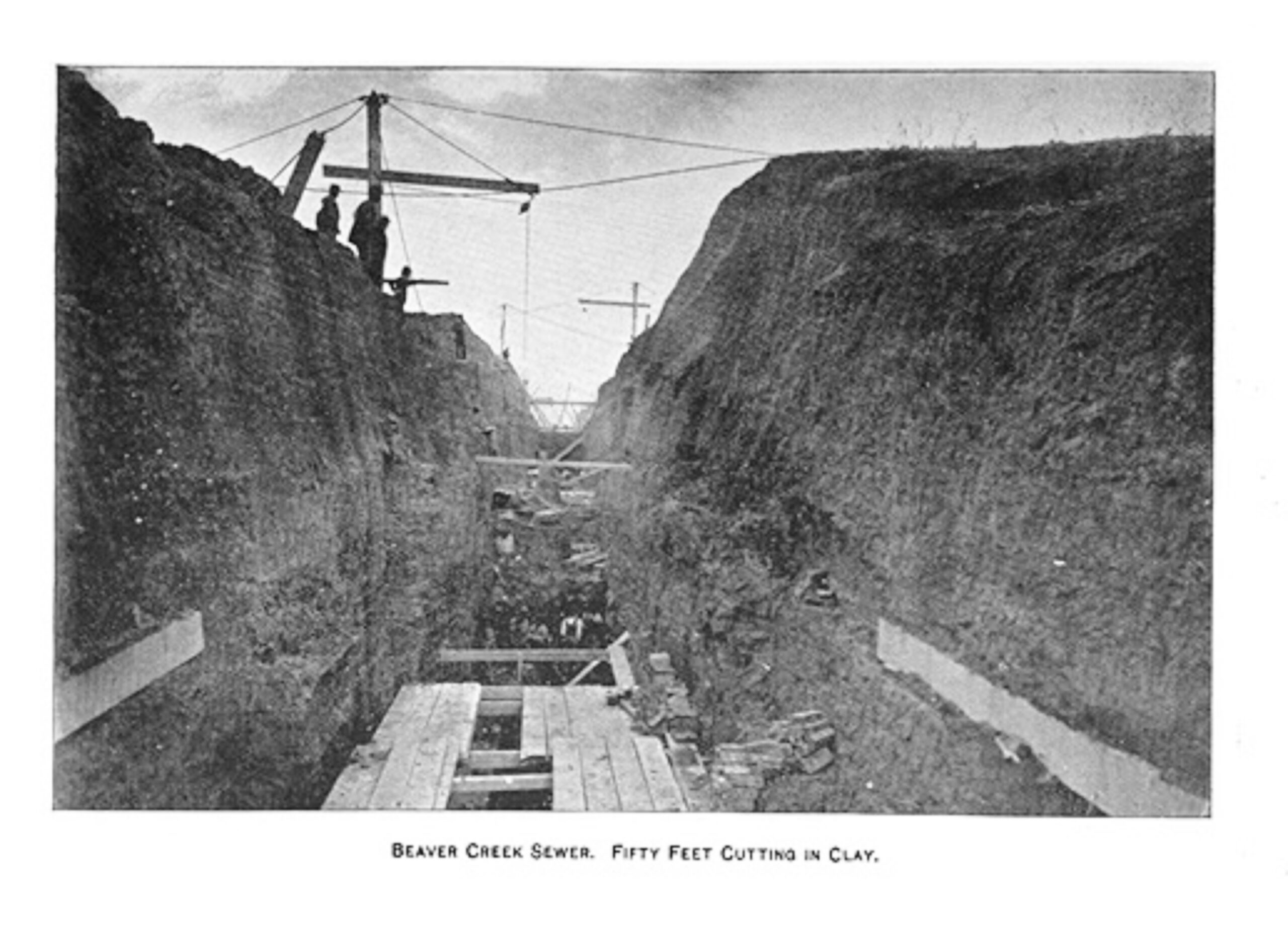

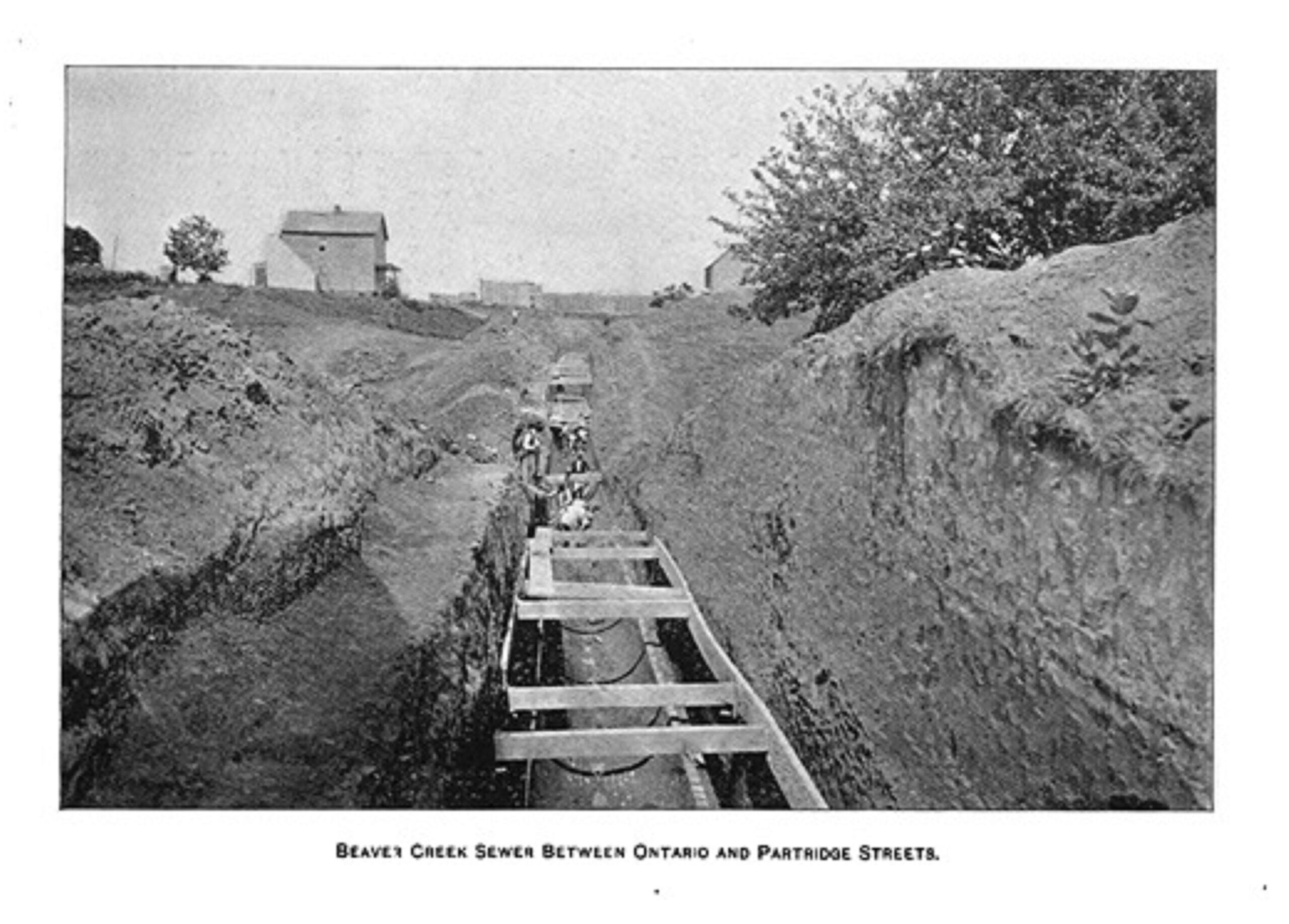

Until 1916, the Bethlehem/Albany town line ran very near the land where the pond now lies [2]. Over time and in stages, the city buried the Beaver Creek, integrating it into the urban sewer system. Around the turn of the 20th century, a shallow spring-fed pond, roughly 1,500 feet long and 200 feet wide, formed from a marshy area west of Marion Avenue [3], [4], [5], [6], [7]. Known for many years as Raft’s Pond, the waterway was part of the Holmes Farm property and bordered by cow paths, a rural scene that belied its urban future [8], [9].

In This Section

Beaver Creek

Residential Expansion

and the Birth of Buckingham Lake

Recreation, Mishaps,

and Community Life

Mosquitoes, Shanties,

and Songbirds

Stonehenge Development Proposals

Advocating for a Nature Sanctuary

Clean-up and Park Land

Buckingham Drive

Sewer Separation

Berkshire Boulevard

Sewer Separation

A Community Commitment: Forming the Buckingham Pond Conservancy

Residential Expansion and the Birth of Buckingham Lake

As Albany expanded—with the annexation of the Bethlehem-held land and the paving of New Scotland Avenue—developers seized the opportunity and the residential neighborhoods expanded westward. By 1925, the developer of “Buckingham Gardens”—a new residential neighborhood south of the pond—promoted the waterway as the centerpiece of its 120-acres of “beautiful building lots,” and renamed the waterbody as “Buckingham Lake” [11]. “This lake lends much to the attractive appearance of the development,” [12] boasted later promotional ads.

Developer plans in 1927 called for extending nearby Lenox and Euclid avenues—which then ended at a crest just north of the Greenway [13]. Later, in 1929, the developers of Buckingham Gardens—Peter D. Kiernan and John J. Cregan—proposed extending Woodlawn Avenue, east of the pond, to meet an extended Lenox Avenue on the north side and continue around the pond. Their plans also included the creation of a residential park [14], with the developers offering land free of charge to the city for public use on the condition that work would begin in two years, an idea supported by the president of a neighborhood citizens’ organization (the Westland Hills Improvement Association) but declined by city officials unable to commit to the deadline [15].

Officials later reversed course, however, and accepted a deed to three acres of land, which the Kiernan/Cregan firm (the Buckingham Investment Co.) donated for a 30-foot-wide concrete boulevard accompanied by planted trees and shrubs around the pond [16].

Although no boulevard was built at that time, and Woodlawn Avenue was never extended to the pond, and then-Mayor John Boyd Thatcher proposed additional amenities—a swimming pool and a skating rink at the park—which never materialized―and the purchase of additional land [17]. The city eventually bought another 13 acres, including the pond itself, from the development company for $13,500 [18], and the pond and surrounding grounds saw early improvements funded by Common Council allocated-funds for Depression-era work relief programs [19]. Grading and clearing of the pond and surrounding land was financed in three city ordinances in 1932 [20].

While exploring the history of how the pond came to be, think about its significance in your lives. If you’d like to share your story of Buckingham Pond, please consider submitting it for publication on this website.

Buckingham Lake 1931, (A) View is thought to be towards the southwest shore (end of Lenox or Euclid Avenue), (B) View is thought to be towards the northeast shore (buildings in the view may be on Lenox Avenue – Western Avenue side), (D) View is thought to be of the western end of the lake (E) View is thought to be towards the northwest shore (near current end of Colonial Avenue), (F) View is thought to be from east end looking west.

Courtesy Dan Hershberg, Hershberg & Hershberg (Civil / Site Engineers and Surveyors), from the collections of the Albany Bureau of Engineering.

Recreation, Mishaps, and Community Life

For many years, Buckingham Pond served as a summer swimming hole [21] and a winter ice-skating venue [22]. The value of the pond and its grounds waxed and waned from a desirable recreational asset to a swampy, vermin-infested nuisance.

In 1930, the Westland Hills Improvement Association illuminated the pond on days from 3 PM to 1 AM for nighttime events, cleared the snow from it and surrounding sidewalks, sponsored carnivals with “fancy” skating, bonfires, and other entertainment [23], and built a toboggan slide and a warming hut [24]. Skating was so popular that, by 1940, Mayor Thatcher dispatched a special police detail to the pond [25]. Because of war priorities, the lights were darkened in 1942, and, by the mid-40s, vandals had destroyed the shelter and the lights, and they were never replaced [26].

Popular as it was, skating could be dangerous. Children occasionally fell through thin ice, leading to rescues by city workers, and injuries on the pond or surrounding land were not uncommon [27], [28], [29], including a 13-year-old girl hospitalized after a head injury in 1954 [30], and several other mishaps [31], including an adult driver who drove into the pond in 1961 and had to be rescued by police [32]. Swimming and skating apparently weren’t the only recreational sport that the pond provided city residents, although some of the activities might not have been legally sanctioned. At least one young man found it a venue for hunting. In 1935, a 17-year-old was arrested for illegally discharging a firearm within city limits after neighbors near the pond reported hearing shotgun fire [33].

Yet the pond also fostered meaningful traditions. In 1965, Temple Israel began holding annual tashlich ceremonies on the pond during Rosh Hashanah high holy days [34], a symbolic casting away of misdeeds—a tradition shared by multiple local temples today.

Did You Know?

Hidden below the City of Albany’s streets, buildings and parks are 900 miles of sewer pipes.

Although parts of the sewer system are more than 100 years old, it works remarkably well—except when there’s a heavy storm.

The City of Albany Water Department completed the Beaver Creek Clean River Project in 2024 to reduce the volume of untreated overflow discharged to the Hudson River.

Mosquitoes, Shanties, and Songbirds:

Buckingham Pond’s Uneasy Evolution

Throughout its history, Buckingham Pond has existed in tension between urban development (and cultivation of the surrounding land) and natural preservation. The city first allocated money to grade and clear the pond and surrounding property in 1932 [35]. Despite these improvements, the area around the pond remained undeveloped by late in that decade, and pests were a problem. Depression-era shanties stood along the termination of Berkshire Boulevard on the north side [36]. The city used a crew of 120 men in a Works Progress Administration project to dig with pickaxes through the swampy land in hopes of eradicating mosquito breeding areas [37]. In 1940, Mayor Thatcher declared the pond a “swampy wasteland” and announced plans to fill it and create a public park in its bed [38]. That plan was never realized, and nearly 20 years later, a newspaper reader called the area “a dumping ground for everyone who drives by.” Still later, a citizens’ committee complained that the land was infested with thousands of rats [39].

Despite these challenges, the pond’s ecological value was recognized early. In 1939, the Sassafras Bird Club of Amsterdam visited for birdwatching, noting the pond as a haven for numerous species [40].

Berkshire Boulevard Shanties, 1939.

Courtesy Dan Hershberg, Hershberg & Hershberg (Civil / Site Engineers and Surveyors),

from the collections of the Albany Bureau of Engineering.

New Scotland and Lenox Avenue intersection 1939 looking west (left) and looking northeast (right).

Courtesy Dan Hershberg, Hershberg & Hershberg (Civil / Site Engineers and Surveyors),

from the collections of the Albany Bureau of Engineering.

Stonehenge Development Proposals

Over the years, competing forces promoted residential and commercial development and the preservation of nature and recreation in the area surrounding the pond. Long after the Buckingham Gardens developers suggested it, newspapers were editorializing in 1935 in favor of a road around the pond that would connect New Scotland and Western avenues [41]. In the late 1930s, the city and WPA funds were employed to hire “gangs” of workers to again clear land around the pond to provide for a “wide boulevard” and open the area for development [42]. Yet in the mid-40s [43], the papers were still referring to “the long-awaited development of Buckingham Lake as the center of a residential community” [44].

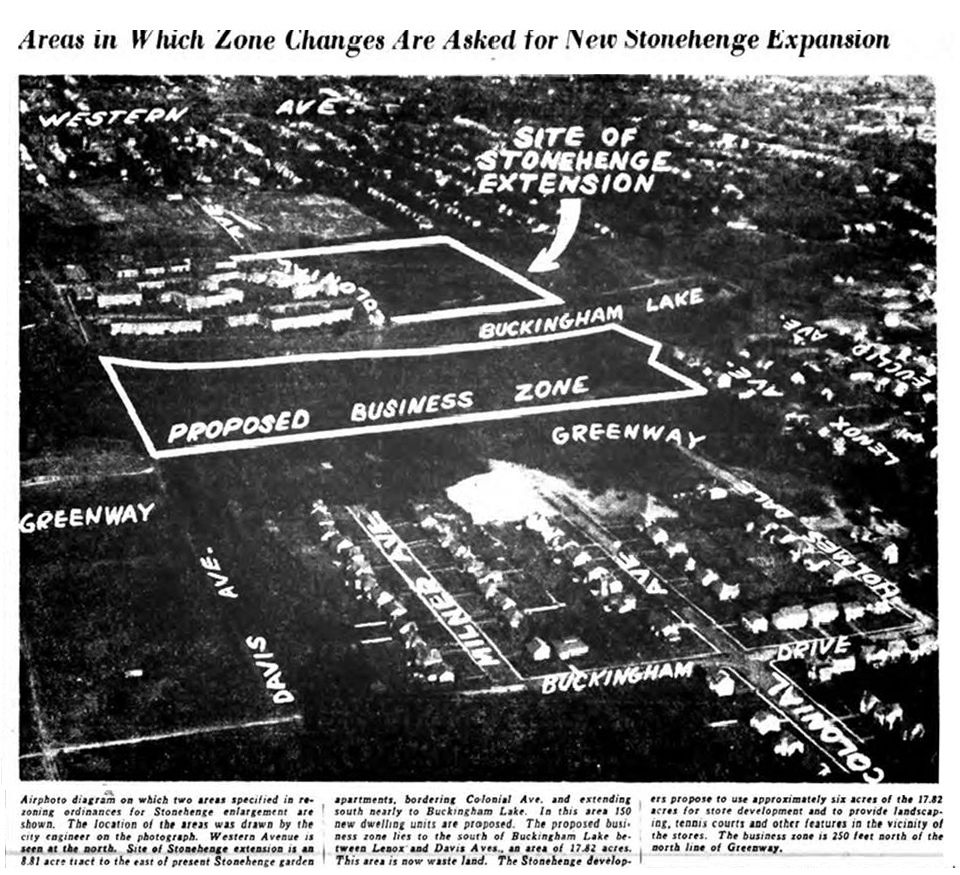

In 1946, Vincent W. Gallagher, the president of the Stonehenge Apartment complex that had been built just north of the pond in the early 40s, proposed an expansion eastward on land that now borders Colonial and Lenox avenues [45]. He also bought 24 acres on the south side of the pond from the Buckingham Investment Co. [46] and asked for a zoning change that would allow the construction of businesses there. His proposed commercial zone would have covered land from what is now Lenox to Davis avenues, south to the Greenway. Gallagher was hoping to build 130 additional apartment units and provide a commercial area for his tenants that would include a grocery, a drug store, a dry cleaner, and a beauty shop.

Newspapers described the proposed business zone as an “unoccupied wasteland of low elevation adjacent to the city-owned Buckingham Lake.” A roadway would be built along the end of Colonial Avenue to provide access to the stores. The project also called for landscaping and the construction of tennis courts.

The Chamber of Commerce supported the project. The Westland Hills Improvement Association opposed it. More than 300 letters on both sides of the issue were sent to the office of Mayor Erastus Corning 2nd [47]. The plan was never approved.

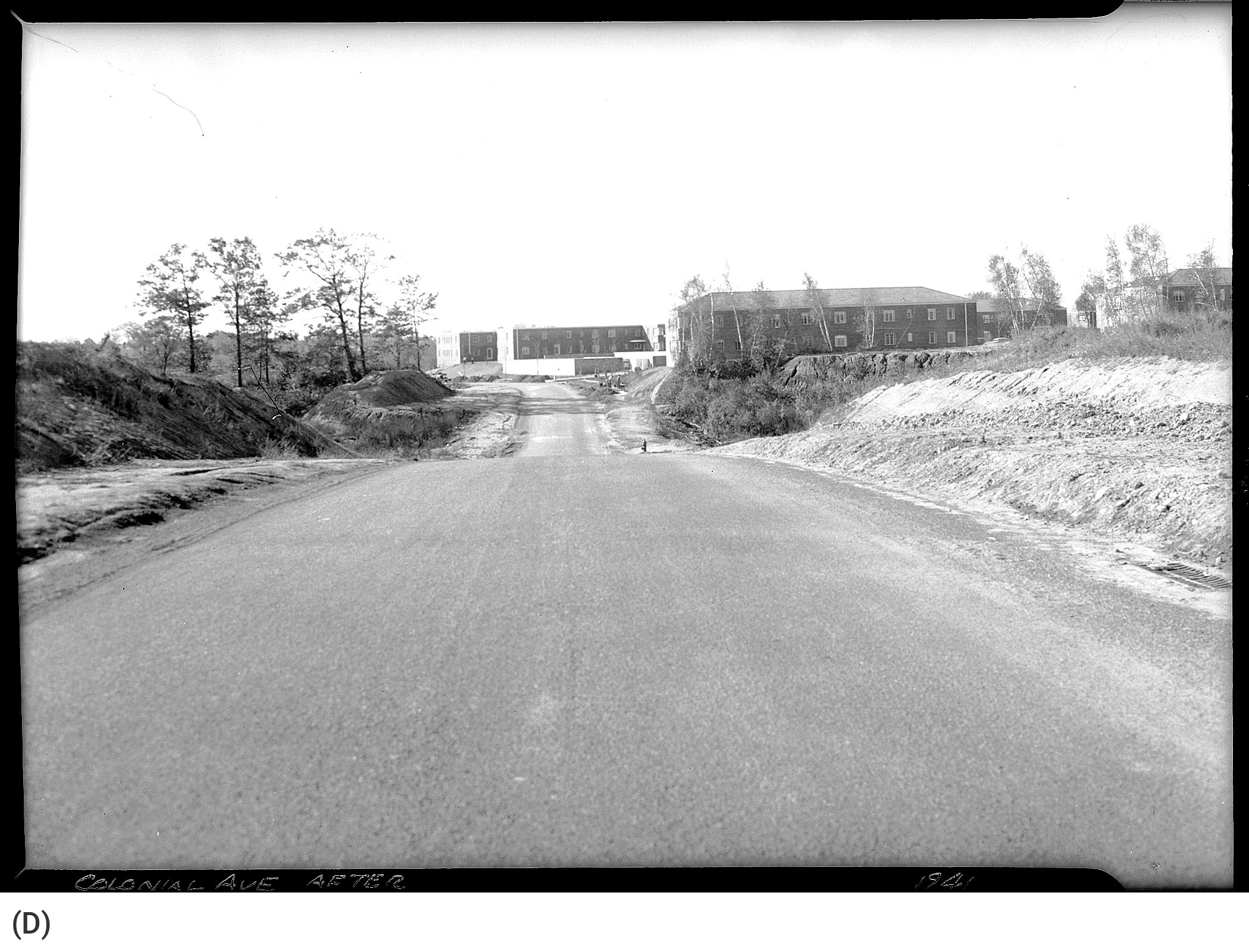

Colonial Avenue and Stonehenge Gardens (on the right) looking towards Buckingham Pond, circa 1941 (A) view thought to be at the end of Colonial Avenue then under construction, (B, C, D) Colonial Avenue under construction in 1941, note Stonehenge Gardens under construction.

Courtesy Dan Hershberg, Hershberg & Hershberg (Civil / Site Engineers and Surveyors),

from the collections of the Albany Bureau of Engineering.

Proposed plans for second stage expansion of Stonehenge Gardens 1946, Albany, NY.

Neighborhood opposition was very vocal and zoning changes were not made.

Courtesy AlbanyGroup Archive Flickr web page [48].

Advocating for a Nature Sanctuary

Others wanted the pond and its environs improved as a nature and recreation area. In 1936, the Wild Life League declared it as a “glorious area” that is “ideal” as a wildlife sanctuary, describing it as a nesting habitat for 40 different species of birds, as well as muskrats, frogs, toads, shrews and woodchucks. “After a little careful management, more species of birds, including possibly wild ducks, may be induced to visit the sanctuary and wing-clipped Canada geese and mallards will add to the charm,” said the state zoologist in endorsing the idea―a remark which now seems prescient given the prevalence of ducks and geese on the water [49]. A newspaper supported efforts to create the sanctuary [50], but ten years later, the idea was still being advanced―this time by another group that suggested a wildlife refuge as a memorial to veterans of World War II [51]. Even later, an anonymous “Albany sportsman” proposed that the city raise the level of the water by three feet and make it a fishing center for kids. Noting that two eagles had been spotted recently at the pond, it should also be considered a refuge for wildlife, the man suggested [52]. But little was done. In 1959, the Nature Conservancy was still calling for restoration and preservation of the pond [53].

Mayor Thatcher’s 1940 proposal to fill the pond and build a park with landscaping and benches and a surrounding carriageway did not come to fruition [54]. But, as the years passed, others had similar ideas that incorporated the pond as a centerpiece. By the early 1960s [55], the area was being described as “a combination pest hole, rat incubator and dumping ground.” An organization named the Citizens’ Planning Committee for Greater Albany called for immediate improvements, including mosquito and rat control, enforcement of “no dumping” warnings, clearing of underbrush, treatment of algae in the pond, paths for bicycles around the pond and night lighting [56]. The group met with Mayor Corning, but nothing was accomplished. Two years later, a representative of the organization declared, “Mayor Corning didn’t say ‘no’ to anything, but he didn’t do anything either.”

The group renewed its recommendations and proposed creation of a bird sanctuary, stocking of the pond for fishing and installation of park benches and picnic tables. “There’s certainly lots of room for a playground,” a spokeswoman added. The citizens’ group also suggested that the city buy vacant land from the owner of Stonehenge Apartments for a park “before this important green area is lost forever” [57].

Clean-up and Park Land

Still, action proved elusive. In 1965, several Democratic candidates for public office presented an architect’s rendering of plans for a recreation area at the pond, and the city hired 36 youths at $1.25 an hour for eight weeks to remove debris and rotted tree stumps on the north shore and to install benches and picnic tables. The money came from the state Division for Youth [58]. In 1972, during another clean-up, grass was mowed and trash cans were installed around the pond [59].

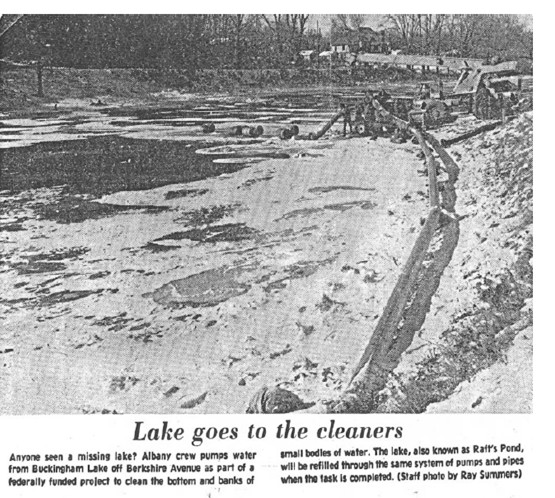

In 1975, the city obtained an additional 7.58 acres adjacent to the pond along Davis Avenue to enlarge the park with the help of aid from the state Division of Housing and Community Renewal [60], [61]. The next year, the Common Council authorized $46,500 to drain and dredge the pond’s bed of between two and 3.5 feet of organic material. Half of the cost was to come from the federal Environmental Protection Agency [62]. In the 1990s, the city’s storm sewer system was diverted from the pond itself, and an adjacent stilling basin was constructed to reduce the impact of storms. Aerators were added to reduce the growth of algae in the shallow waters [63].

Buckingham Lake dredging, Times Union, December 1976. Courtesy Dan Hershberg.

A small playground―with a slide, monkey bars and some green, rocking “dinosaurs” for young riders―was installed on the north side of the pond, next to a parking area that was once a turn-around for a Colonial Avenue bus line [64].

It wasn’t until the administration of Mayor Thomas M. Whalen, III, in 1986 that a trail for walking and jogging was finally laid around the pond. “The Mayor wanted to do something for uptown,” the city parks commissioner noted in announcing plans for a 0.75-mile, four-foot-wide trail of crushed stone to circumnavigate the pond at a cost of $37,760. It would be the only trail in the city at the time dedicated to walking and jogging [65]. Describing the area as “quite unique,” Commissioner Richard Barret declared, “one of the nicest things is the scenery, and the setting is beautiful” [66]. Mayor Whalen, who lived nearby, patronized the trail and ensured that it was well maintained. “I walked [the new trail around Buckingham Pond] last night, and it needs some work…” he wrote Commissioner Barret after one sojourn [67].

In 1994, the city zoned the area known as Buckingham Lake Park as a land conservation zone, permitting only “parks, playgrounds, outdoor recreation and nature preserves or wildlife refuges” [68]. It is not, however, “dedicated parkland” that can never be “alienated” from that purpose other than by action of the state legislature [69].

Buckingham Drive Sewer Separation (1988 – 1989)

In 1988 and 1989, a sewer separation project was completed in two phases. The area was along Buckingham Drive and portions of Friebel Road, Tampa Avenue, Ormond Street, Davis Avenue, Milner Avenue, Colonial Avenue and Holmes Dale which were tributary to the Buckingham Drive combined sewer. The area of sewers separated also included portion of New Scotland Avenue. All street catch basins were connected to a new storm drainage system which discharged into a tributary of the Krum Kill. Thereby the drainage from approximately 51 acres of the Beaver Creek Sewer District was removed from the Hackett Boulevard Sub-Trunk Sewer which had been seriously overloaded [70].

Berkshire Boulevard Sewer Separation (1993 – 1995)

In 1993 through 1995, a multiple phase project was undertaken to separate the storm drainage from existing sanitary sewers in the vicinity of Berkshire Boulevard. The area included drainage that was tributary to a main collection trunk along Berkshire Boulevard and was bounded generally by Lenox Avenue on the east, by Orlando Avenue on the west, by Western Avenue on the north and by Greenway on the south. Most of the storm drainage separated from the sanitary flows was diverted to a stilling basin constructed at the west end of the Buckingham Lake. A pump station was installed which directs the storm water to a NYS drainage line which runs along Route 85 Bypass to the Krum Kill, from a watershed area of approximately 270 acres [71].

The Armory Center made improvements to the pond as part of a wetland mitigation project for improvements on their site. At this time, interpretive signs were added, as were fountain type aerators for oxygenation were added as was a water fill pipe to fill the pond with municipal water in times of drought.

A Community Commitment:

Forming the Buckingham Pond Conservancy (2009)

The Buckingham Pond Conservancy got its start in January 2009 [72], when 33 neighbors came together for an energetic kickoff meeting. Everyone agreed the group should be a lasting, active non-profit advocacy organization—one that learns about the pond’s current conditions, partners with other community groups, builds a volunteer program, and works closely with the City. Soon after, the Steering Committee began meeting with City officials, gathering information, and shaping the Conservancy’s mission and governance.

Since 2009, the Buckingham Pond Conservancy—together with committed board members, neighbors, donors, and volunteers—has worked steadily to protect this urban oasis. With a mission to coordinate existing resources and identify new resources devoted to protecting, preserving, and enhancing Buckingham Pond and its surrounding green space advancing, the Conservancy’s efforts help ensure the pond remains a cherished place for today’s residents and future generations, supporting neighborhood quality of life and providing thousands of people with a nearby, natural space for everyday recreation and well-being.

In 2018, the Conservancy raised money for the purchase and installation of new and expanded playground [73] equipment, including a climbing dome and other attractions for older children. Funds were donated by the Lobo Family in memory of Angelo and Victoria Lobo, Stonehenge Gardens Apartments, Dolores Hamilton, the Bender Family Foundation, the Wildflower Fund, the City of Albany and personal contributions of Albany residents and friends of the pond.

It took nearly a century of advocacy, planning, preservation and development, but what was once a rural wasteland now provides a 15-acre urban oasis around a 5-acre pond of 2 to 6 feet in depth in a residential neighborhood that has been described as “like living in the city, the suburbs and the country―all at the same time” [74].

Notes

[1] William Kennedy, O Albany: An Urban Tapestry (The Viking Press, 1983), 73-74. See also Frederick W. Beers, “Portion of Albany County and city of Albany, Map 33” (Watson & Co., 1891). David Rumsey Map Collection, November 20, 2025, https://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/s/2i3788.

[2] Daniel R. Hershberg, “Buckingham Lake/Berkshire Pond/Raft’s Pond: Some Historical and Other Information About This Waterway” (Presentation to Buckingham Pond Conservancy, 2009), 5. See also City Annexation Map, Albany County Hall of Records (1916). See also F.W. Beers, Map 33 (1891).

[3] Issued in 1873 from official records furnished by Reuben H. Bingham, city surveyor, the Albany City Survey map shows the Beaver Creek path. Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library. “City of Albany, New York” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed November 21, 2025. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/e5138d10-0597-0134-3d7b-00505686a51c.

[4] An 1889 city survey map by Sampson, Murdock & Co. shows Beaver Creek and its path along the Albany city line with Bethlehem. Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library. “City of Albany, New York: from official records furnished” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed November 21, 2025. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/96971f20-0672-0134-96bc-00505686a51c.

[5] An 1894 U.S. Geological Survey, show the Beaver Creek, but no pond. See Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library. “Albany and vicinity” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed November 21, 2025. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/e08f2ce0-0a30-0134-a674-00505686a51c.

[6] The U.S. Geological Survey map of 1898, reprinted in 1907, shows no pond. “USGS ALBANY, NY HISTORICAL MAP GEOPDF 15X15 GRID 62500-SCALE 1898” USGS Store. Accessed November 21, 2025. https://store.usgs.gov/product/893232. See also Times-Union, Sept. 26, 1925.

[7] The pond does appear on a U.S. Geological Survey map from 1927, and the Beaver Creek is a lot shorter. “ALBANY, NY HISTORICAL MAP GEOPDF 15X15 GRID 62500-SCALE 1927.” USGS Store. Accessed November 21, 2025. https://store.usgs.gov/product/893234.

[8] Knickerbocker News, Dec. 13, 1937, Jan. 1, 1940, June 4, 1953. See also Times-Union, Jan. 4, 1938; May 22, 1938; July 22, 2007. The origin of the name “Raft” is a mystery; no property owner by that name appears on early maps.

[9] Our Facebook friend Al Quaglieri wrote on our post of June 19, 2024: [I went] “on a little unproductive goose chase seeking the origin of the name Raft’s Pond. I came up dry, but I did learn some things in the process. First, the area south of Western from Manning to about Lenox was owned by farmer Jacob Holler. Holler was a German immigrant who made good for himself as a building contractor, major projects all over the city, including the West Albany Shops. He called his plot West Lawn. Starting around 1913, he sold it to the E. Del. Palmer company, who divided it into 500 lots and sold them to the public. From Lenox westward―including both sides of the Western Turnpike as far as the Country Club―was owned by farmer Thomas Holmes, who hailed from Lincolnshire, England. This included the pond in question. The elder Holmes died in 1885 and his sons took over the properties. Son Thomas Harvey Holmes owned the land but refused to sell to speculators until relenting in 1927 in a deal with the Buckingham Investing Company. Incorporated in 1914, Buckingham chose to make the swampy pond into a selling point (this is most likely when Raft’s Pond became Buckingham Lake). In 1931, John J. Cregan, the developer of Buckingham Lake, turned over the pond and the hundred feet surrounding to the City of Albany, who would become responsible for the lake’s maintenance and the road circling it.”

[10] “Beaver Creek Sewer System c 1896 Albany NY 1890s,” Courtesy AlbanyGroup Archive Flickr web page. Accessed November 21, 2025. https://flic.kr/p/p8NtGx, and https://flic.kr/p/pS5iTn.

[11] Times-Union, Sept. 26, 1925.

[12] Times-Union, Sept. 24, 1927.

[13] Sampson & Murdock Co. Inc, “Map of the cities of Albany and Rensselaer, New York (1926). American Geographical Society Library, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries. Accessed November 11, 2025. https://collections.lib.uwm.edu/digital/collection/agdm/id/3178. See also Albany Evening Journal, Sept. 10, 1927.

[14] Knickerbocker News, Feb. 17, 1929

[15] Times-Union, Sept. 21, 1931; Sept. 17, 1928; June 8, 1930.

[16] Times-Union, Sept. 21, 1931; June 23, 1932.

[17] Times-Union, Jan. 3, 1930.

[18] Knickerbocker News, Sept. 22, 1931.

[19] Albany Evening Journal, June 20, 1932.

[20] Minutes of the Common Council (Jan. 13, 1932; June 20, 1932; Dec. 8, 1932), Albany Public Library Local History Room.

[21] Knickerbocker News, Nov. 16, 1961.

[22] Times-Union, Jan. 1, 1938.

[23] Albany Evening Journal, Dec. 18, 1930; Jan. 22, 1931.

[24] Albany Evening News, Dec. 24, 1930. See also Knickerbocker News, July 20, 1961.

[25] Knickerbocker News, Jan. 4, 1940.

[26] Knickerbocker News, Dec. 22, 1942, July 20, 1961.

[27] Knickerbocker News, Dec. 4, 1944.

[28] Knickerbocker News, December 1953.

[29] Schenectady Gazette, Dec. 27, 1933.

[30] Knickerbocker News, Dec. 31, 1954, Jan. 17, 1955.

[31] Times-Union, Dec. 26, 1936. See also Ballston Spa Daily Journal, Dec. 26, 1936.

[32] Knickerbocker News, Aug. 8, 1959, Mar. 20, 1961.

[33] Knickerbocker News, Oct. 30, 1935.

[34] Times-Union, Sept. 25, 1965.

[35] City Ordinances, Jan. 13, 1932, June 20, 1932, Dec. 8, 1932.

[36] Daniel R. Hershberg, “Buckingham Lake/Berkshire Pond/Raft’s Pond: Some Historical and Other Information About This Waterway” (Presentation to Buckingham Pond Conservancy, 2009), 13

[37] Knickerbocker News, Nov. 29, 1936.

[38] Knickerbocker News, June 4, 1940.

[39] Knickerbocker News, June 11, 1959, July 20, 1961.

[40] Amsterdam Daily Democrat and Recorder, Sept. 27, 1939.

[41] Knickerbocker News, Nov. 28, 1935.

[42] Times-Union, May 22, 1938.

[43] The streets around the pond are shorter than present day, as shown in a 1947 U.S. Geological Survey map. “ALBANY, NY HISTORICAL MAP GEOPDF 15X15 GRID 62500-SCALE 1947.” USGS Store. Accessed November 21, 2025. https://store.usgs.gov/product/893233.

[44] Knickerbocker News, Mar. 29, 1946.

[45] Knickerbocker News, Feb. 20, 1946.

[46] Times-Union, Mar. 30, 1946.

[47] Knickerbocker News, Feb. 20, 1946.

[48] “Proposed plans for second stage expansion of tonehenge apts 1946 albany ny 1940s.” Courtesy AlbanyGroup Archive Flickr web page. Accessed November 21, 2025. https://flic.kr/p/gYjHZx.

[49] Knickerbocker News, Nov. 29, 1936.

[50] Knickerbocker News, Jan. 23, 1937.

[51] Knickerbocker News, Feb. 19, 1946.

[52] Knickerbocker News, Aug. 21, 1948.

[53] Knickerbocker News, Dec. 16, 1959.

[54] Knickerbocker News, June 4, 1940.

[55] By the 1950s, development around the pond is limited still, as shown on a 1950 U.S. Geological Survey map. “ALBANY, NY HISTORICAL MAP GEOPDF 15X15 GRID 62500-SCALE 1950.” USGS Store. Accessed November 21, 2025. https://store.usgs.gov/product/893236.

[56] Knickerbocker News, Aug. 16, 1961.

[57] Knickerbocker News, Aug. 16, 1961.

[58] Knickerbocker News, Sept. 10, 1965, Sept. 11, 1965.

[59] Knickerbocker News, July 5, 1972.

[60] Minutes of the Common Council, June 2, 1975. See also “Deed,” Sheber Development Corp. to City of Albany, Oct. 23, 1975.

[61] By 1978, Milner, Colonial, and Holmes Dale were extended to the pond, and Rafts Way appears on the 1978 U.S. Geological aerial map that shows the pond-side ends of the streets under construction. USGS Store. “ALBANY, NY HISTORICAL MAP GEOPDF 7.5X7.5 GRID 24000-SCALE 1978.” Accessed November 21, 2025. https://store.usgs.gov/product/891647.

[62] Minutes of the Common Council, Aug. 9, 1976. See also Letter from John V. DiGiulio, Dec. 10, 1976. See also Hershberg, Daniel R. Hershberg, “Buckingham Lake/Berkshire Pond/Raft’s Pond: Some Historical and Other Information About This Waterway” (Presentation to Buckingham Pond Conservancy, 2009), 20.

[63] Daniel R. Hershberg, “Buckingham Lake/Berkshire Pond/Raft’s Pond: Some Historical and Other Information About This Waterway” (Presentation to Buckingham Pond Conservancy, 2009), 3, 29-34.

[64] Daniel R. Hershberg, “Buckingham Lake/Berkshire Pond/Raft’s Pond: Some Historical and Other Information About This Waterway” (Presentation to Buckingham Pond Conservancy, 2009), 39. See also Knickerbocker News, July 5, 1972.

[65] Times-Union, Mar. 28, 1987

[66] Times-Union, Oct. 19, 1986.

[67] Daniel E. Button, Take City Hall (Whiston Publishing Co., 2003).

[68] Letter from Willard A. Bruce, Jan. 19, 1994.

[69] Al Lawrence, “Dedicated Parkland,” March 28, 2010.

[70] Daniel R. Hershberg, “Buckingham Lake/Berkshire Pond/Raft’s Pond: Some Historical and Other Information About This Waterway” (Presentation to Buckingham Pond Conservancy, 2009), 2.

[71] Daniel R. Hershberg, “Buckingham Lake/Berkshire Pond/Raft’s Pond: Some Historical and Other Information About This Waterway” (Presentation to Buckingham Pond Conservancy, 2009), 3.

[72] “About The Conservancy,” Buckingham Pond Conservancy website. Accessed November 21, 2025. https://buckinghampondconservancy.org/about-the-conservancy/.

[73] “Memorandum of Understanding Between The City of Albany and The Buckingham Pond Conservancy,” Aug. 10, 2017. As part of the Memorandum, the Conservancy raised the money and the City, including the Department of Parks and Recreation maintains the playground.

[74] Times-Union, July 22, 2007. See also Department of Environmental Conservation, “Buckingham Pond.” Accessed November 21, 2025. http://dec.ny.gov/places/buckingham-pond.

Buckingham Pond has a way of making an impression, leaving a mark on the lives of those who have experienced it.

Perhaps as a teen, you remember a romantic moment on an unlikely concrete bench or a pick-up hockey game on the square of ice cleared for skating. Or as a parent, you experienced joy in passing on the love of fishing or in watching your child’s surprise at spotting a snapping turtle, or giant koi. Or as a bird enthusiast, you found delight in an unexpected great blue heron. Or walked around the pond every morning and felt the gratitude of your four-legged dog friend after getting treats from a friendly caretaker (for those of you who remember Jack). Or simply watched the snow fall silently on the frozen lake. We invite you to send us your stories, and with your permission, we will publish them on the website for others to enjoy.

What Is Your Story?

SHARE WITH US YOUR BUCKINGHAM (OR RAFTS) POND MEMORIES

Please use the form below or email the Buckingham Pond Conservancy at [email protected] to submit your story for consideration

and publication on this website.

Looking for ways to help?

You can help ensure that Buckingham Pond is enhanced

for generations to come! Volunteer for events.

Become a BPC member. Donate. Join the BPC Board.